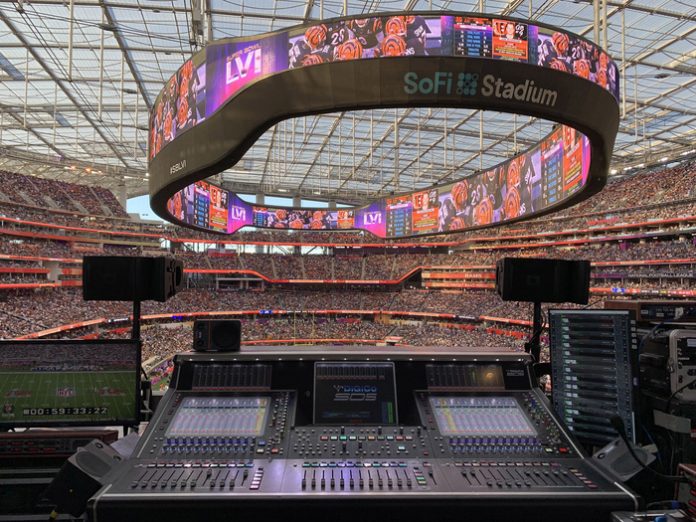

This year’s Super Bowl LVI at SoFi Stadium in the Los Angeles area was an inflection point for the event’s signature halftime spectacular. It was to be the first time that all of the music performers were hip-hop artists, reflecting a shift what has taken place over the last decade that has seen the genre come to dominate popular music sales, charts, and culture. One thing that has remained a constant, though, was the event’s reliance on DiGiCo as ATK Audiotek, now a Clair Global company, once again deployed four SD5 mixing consoles to handle the complex and high-profile production.

The headliners—Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Eminem, Mary J. Blige, Kendrick Lamar, and surprise guest 50 Cent—were intended to constitute what halftime sponsor Pepsi called “…the greatest 12 minutes in music entertainment the world has ever seen.” A bit hyperbolic, certainly, but characteristic of the NFL’s view of its own place in the cultural hierarchy, one in which superlatives are everyday parts of speech. And while the event may have been culturally momentous, it also brought along implications for its live sound and audio, especially considering the bass-heavy nature of the genre. As with previous years’ halftime events, ATK Audiotek augmented the host stadium’s installed sound system with additional speakers and amplifiers loaded onto bespoke wheeled carts to accommodate both the substantial low end as well as the crisp vocal intelligibility required.

Getting the front-of-house and monitor mixes together called for a team as good as the LA Rams and the Cincinnati Bengals, who were playing the match. They found that in Alex Guessard and Tom Pesa, veteran TV music mixers who had both worked the 2017 Super Bowl halftime show that featured Lady Gaga, as well as a slew of Grammys, Oscars, and other awards shows as well as American Idoland Billboard Music Awards shows. They in turn were paired with two pairs of DiGiCo SD5 consoles, one each for FOH and monitors and one more each as redundant backups. When you only have 12 minutes for what is arguably the premier televised music event of the year, you don’t take any chances.

All four consoles were on an Optocore networked loop that extended from the playing field, where over 100 volunteers were choreographed to move into place the pieces of the complex music stage, to the mid-level position in the 400 tier where Guessard mixed the show’s live sound from, and to the stadium’s rack room, where Pesa mixed IEMs and wedges while watching on a program monitor. They were also connected via a Riedel point-to-point intercom and partyline intercom matrix. Two DiGiCo SD-Racks served as stage boxes, while a pair of DiGiCo Orange Boxes converted Optocore to MADI to utilize Focusrite RedNet D64R units for MADI-to-Dante conversion for distribution to the NFL building studio. “Pretty much everything was interfaced with MADI or directly onto the DiGiCo loop,” says ATK Audiotek System Design Engineer Kirk Powell.

They were also able to take advantage of the surfeit of dark fiber installed as part of the newly opened SoFi Stadium and its surrounding campus. However, it’s single-mode fiber there, while the DiGiCo desks are normalized for multimode fiber. To accommodate that and the longer distances in the stadium, Powell says they switched the transceivers to single mode.

Monitor World

This was Tom Pesa’s 26th Super Bowl halftime event, but each one is so unique that no sense of it being simply an ordinary show ever has a chance to materialize. The pre-game music events were a warm-up for the crowd and for him, feeding Shure PSM 1000 IEMs to both vocalist Jhené Aiko and harpist Gracie Sprout for “America The Beautiful,” then to rising country music star Mickey Guyton, who sang “The Star-Spangled Banner.” However, that doesn’t prepare one for the sheer SPL that poured onto the field once the hip-hop performances began, led by Dr. Dre, who joined with Snoop Dogg on the opening joint “The Next Episode,” and then segued into “California Love,” 2Pac’s Dre-produced hit that shouts out Watts, Compton, and Inglewood, meaningful neighborhoods in L.A. rap culture and all within a short low-rider jaunt of the venue.

Pesa, who estimates that it was the loudest halftime show in the event’s 50-plus-year history, says his task was to keep the monitors tight for each of the six artists and their RF microphones. “It’s important that the vocals not get washed out by the reverberation of the delayed return from inside the stadium,” he explains. Interestingly, it’s another form of reverb that helps him accomplish that. Pesa uses the vocal plate reverb setting on the SD5’s internal processing. “Adding a touch of the plate with a bit of slap to the monitors acts as an enhancement in the in-ears,” he says. “The stadium itself is taking care of the main reverb. This gives the monitor sound a different texture that helps keep it distinct. I’ll also use the onboard compression and multiband EQ. I prefer the stable environment that the console’s own processing gives me. I also like that I have all of the processing right there at my fingertips.”

Pesa usually works with the artists’ own monitor mixers in the rehearsals prior to the event, but for this year’s event one person, Jaymz Hardy-Martin III, acted as the collective spokesperson for most of the performers; Ryan Cecil, Eminem’s monitor mixer, was also on hand during rehearsals. “Everyone has notes for their artists’ expectations and it comes together pretty smoothly,” he says.

Out Front

Alex Guessard has also worked a double-digit number of Super Bowl halftime shows, 13 in total, including six as both the front-of-house mixer and system designer. He has truly heard it all when it comes to the massive venues the shows call home. “The stadiums aren’t really designed for music shows,” says Guessard, who also designs the temporary JBL-equipped wheeled-cart sound systems deployed for Super Bowl halftime performances. “They’re designed to amplify the noise of the hometown crowd. This year the reverb time was about eight seconds, which was OK, but in the past, it’s been as long as 10 seconds or more. It’s a challenging environment in which to mix music.”

Guessard says he’s come to rely on DiGiCo desks to help navigate such environments. “For mixing, the SD5 is a fast console, the way it’s laid out,” he says. “The bells and whistles are there, but so is the intuitive workflow design. I can access every fader I want quickly and accurately.” But he reserves his highest plaudits for the SD5’s ability to sit in a carefully crafted and highly redundant network scheme, along with a pair of SD-Racks and two DiGiCo Orange Boxes, the latter used to bridge between MADI and Dante and MADI and the Optocore loop all of these units shared at the show. “Through the Orange Boxes, I was getting signal from two different signal paths to the two SD5 consoles running in mirror mode, which gave us complete failover protection,” he says. “That way, I could keep mixing no matter what happened.”

As is typical on hip-hop shows, there were some pre-recorded tracks used by the performers, as well as the live vocals and several live instruments, including a cool piano beat by Dre. Guessard estimated that there were over 50 input channels on the show, all requiring sure, fast moves as the performers shifted on stage. “The SD5 makes sure I can find every input I need exactly when I need it,” he says. “It’s the console you want on your team for this show.”